How Tyler, the Creator got me into college

When I was fifteen years old, I had an indescribable, all-consuming obsession with an up-and-coming rapper named Tyler, the Creator. I listened to every song, had notifications turned on for every one of his tweets, and watched every interview and vlog of his I could find.

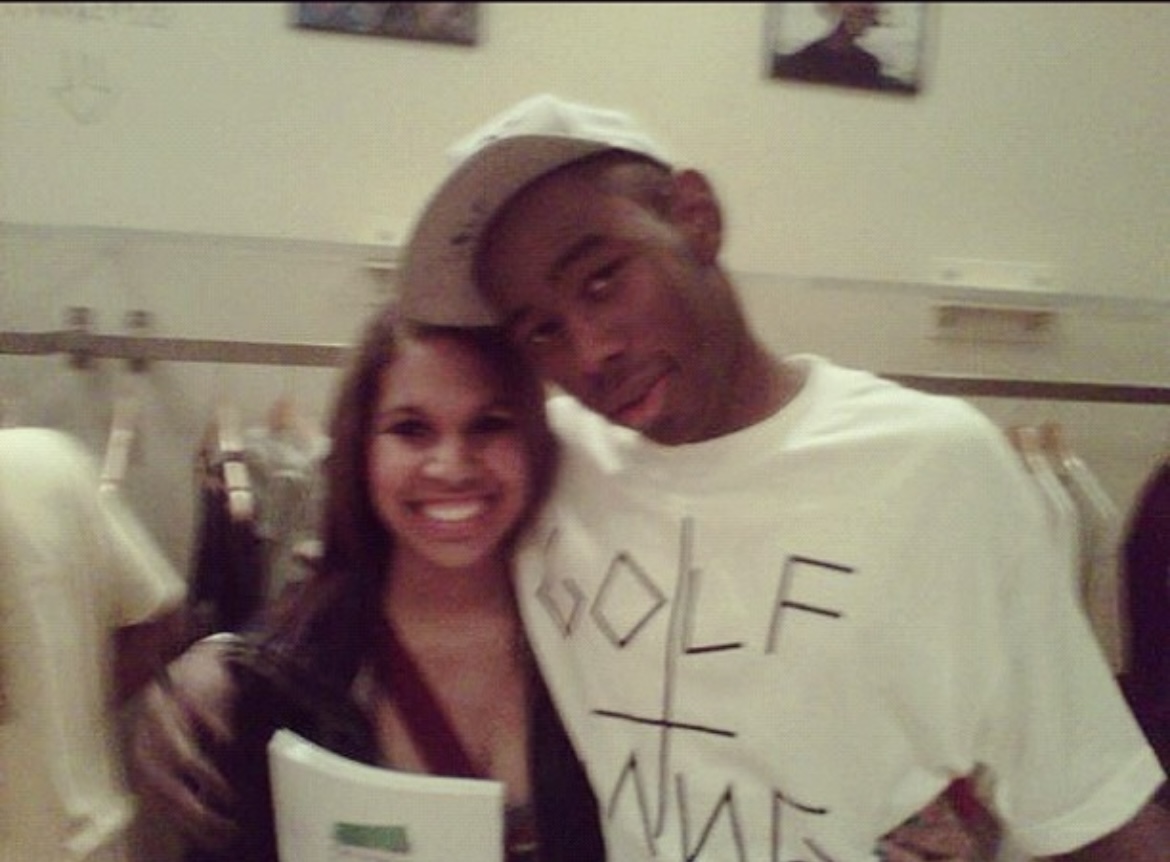

In October of that year, I waited in a six-hour line at the grand opening of his Odd Future store on Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles, CA. When I finally reached the front of the line, I met Tyler. We took a picture, he told me I had pretty teeth, and I bought a photography book and tank top. For years, I never washed the shirt I was wearing while I met him. It was literally the best day of my life up until that point.

This is the picture of Tyler & I (There was a no photo policy in the store but he made an exception for me, because I was practically hyperventilating, saying, "Someone take a picture of us before she passes out.")

I saw a bunch of street banners advertising UCLA while waiting in line. I assumed the campus was close by, not knowing anything about LA's geography or traffic. That day changed the trajectory of my life and was the birth of my "dream school." My goal was clear: I would gain acceptance to UCLA, putting me in clear proximity to Tyler's store which would allow me to be around him often enough for us to fall in love and get married.

The second part of the goal never came to fruition; I very rarely went back to his store. The first part of the goal, however, did come true on March 21, 2014. This became the new best day of my life. Little had I known, my unhealthy obsession with a rapper would lead to my acceptance to UCLA.

Once I got to UCLA, I realized my journey there was unlike the rest of my peers. In the words of Claire Vaye Watkins, "All educations, [I] realized then, are not created equal." In The Ivy League was Another Planet, Vaye Watkins tells her college admission story. Growing up in rural Pahrump, Nevada, population 44,738, she explains, "By the time they're ready to apply to colleges, most kids from families like mine--poor, rural, no college grads in sight--know of and apply to only those few universities to which they've incidentally been exposed."

This blog by Professor Pruitt explores Vaye Watkins article in more detail.

Growing up in Merced, California, was similar in a lot of ways to Vaye Watkins in Pahrump but also very different. Merced is a mid-sized, agricultural city in the middle of the central valley, but it also the home of the University of California's newest campus, UC Merced and Merced Community College. Moreover, twenty minutes north is California State University (CSU), Stanislaus and fifty minutes south is CSU Fresno. It is a great privilege to grow up surrounded by so many options for higher education, one that many rural students don't enjoy.

For the most part, however, I learned of these schools because of proximity or incidental exposure, not because they put any effort into recruiting my classmates or me. Like Watkins' high school, the only recruiters that came to Merced High were military recruiters. And their efforts were rewarded. We loved the college-aged men coming to our school, getting us out of history class to go into the quad and engage in pushup and pull up challenges. They bragged to us about seeing the world, buying brand new Mustangs and Camaros, and making double the money for simply being married. Sarina Mugino discusses military recruitment, and military marriages, in more detail in this blog. At my high school graduation, a small group of us were going off to a university, but plenty of others stood to be honored for enlisting in the military.

Ivy League schools were truly another planet. I couldn't even name any outside of Harvard and Yale. I often got Stanford confused with CSU Stanislaus. I knew absolutely nothing about the vast range of prestigious universities throughout the country.

I applied to eight schools because I qualified for a fee waiver that granted me four free CSU applications and four free UC applications. At seventeen, my choices were based on location. I knew practically nothing about any of the schools, but I knew UC Santa Barbara, UC San Diego, and San Diego State University were by the beach. I knew CSU Chico was known for parties. I knew UC Irvine, CSU Humboldt, and CSU Northridge were far enough away from my hometown that I could distance myself and begin healing from the difficult environment I grew up in.

Outside of Tyler, the Creator, UCLA also had one thing no other school had. It had prestige. The day I proudly announced to my geometry class that I planned to go to UCLA I had no clue of its prestige or small acceptance rate. After my announcement, two of my classmates burst out laughing, telling me that "like 5% of people accepted there are Black" and I wouldn't qualify to join that small number. I will always remember my geometry teacher, Mr. Aguayo, for adamantly and immediately sticking up for me by saying his brother, "who was a lot less smart than me," graduated from there and Riki could, too.

Unfortunately, Mr. Aguayo was an exception to the norm. It became a pattern for people to doubt my dream. Repeatedly, I was told I would not be admitted. These messages came from classmates, teachers, an assistant principal, and probably many more people behind my back. Eventually, I allowed the doubts to erode my enthusiasm until I stopped telling people my dream. In fact, by UCLA's decision day, I told all my classmates I wasn't going to check because I would never go to UCLA anyways. I will always regret waiting to read my acceptance until I was at home and all alone. I wish I had trusted myself more.

In hindsight, the people who doubted me knew something I, very thankfully, had no clue of--the resources of the students I was up against.

I took my SATs twice, with no studying beforehand. I had straight As, but from a low-funded, low-performing high school. Most shocking of it all, to me, is that little seventeen-year-old me submitted every part of my college applications through my iPhone because my family had no computer. I wrote my personal statement and scholarship essays in my notes app, copy and pasting straight from there to admissions portals.

I've worked in college admissions since I was nineteen and I've seen over and over how unequal educations are. With my current company, students start their college preparation as early as middle school. They are assigned a tutor for every subject they can't get an A in. They begin our rigorous, years-long SAT/ACT prep. They are assigned a college counselor who studies their transcripts, extracurricular activities, interests, etc. and curates a perfect college list for them that ranges across the country. And, before the applications even open, essay coaches, like me, fine comb through every word on each and every one of their applications, using our CEO's essay writing formula, until each is polished to perfection.

I look back at my own college application efforts and I truly marvel that I ever stood a chance.

In some ways, I think there is a privilege in growing up a world away from the Ivy Leagues. I still remember the unexplainable joy I got reading I was accepted into my first college, San Diego State. I ran to my mom's room and we both cried, repeating over and over, "we're going to college." She immediately asked me to send her a screenshot so she could brag on Facebook. For us, honestly, any college was a dream.

But I was lucky enough to grow up in California. Even my "safety" schools were great schools. There are many students for whom UCs and CSUs are on another planet, and many for whom even community college is in another universe. Watkins ends her article with a very powerful question, "...is it any wonder that students in Pahrump and throughout rural America are more likely to end up in Afghanistan than N.Y.U.?" From my experience, there is no wonder in this at all.

This post, by Geovanna, goes into detail about other risks that hold rural students back from receiving college educations.

Labels: pop culture, rural, self discovery, Success